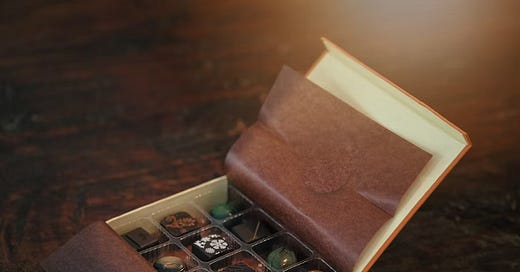

Moscow, April 1962, a young woman is pushing a pram in a Moscow park. A Russian man approaches. He quickly compliments the baby and drops a small box inside the pram. The young woman is Janet Chisholm, wife of Ruari Chisholm, the MI6 Chief of station in Moscow. The man is Oleg Penkovsky, a Colonel in Russian Military Intelligence (GRU). The box he has just dropped looks like a box of chocolates, but contains microfilms and papers detailing Soviet military information. Penkovsky is a spy, one run jointly by the CIA and the British MI6.

Photo by Clint McKoy on Unsplash

The encounter, quick, and meant to look casual is called a “brush contact” or a brush pass. It is a method intelligence officers and the spies they recruit use to pass information. It is generally quick, public, and aimed at eluding surveillance. It has the appearance of a chance encounter or maybe a bump into each other. A small parcel or an item containing information is passed, at times hidden in other items such as newspapers. A game of symbols is also involved for the spies to be able to recognise each other.

The Brush contact: a new substack

“The brush contact” is also the name of my foray in the world of substacks. Like an actual brush contact, this substack will discuss small - but hopefully interesting - bits of information. It will cover intelligence-related matters, with a primary focus on covert operations and state-sponsored assassinations.

The information will come from a broad range of sources, things I am reading, podcasts I listen to during dog walks, movies and TV series. The idea is to take a few snippets from these sources, add a couple of personal reflections and - in the meantime - connect with existing works and material on the topic. I am not sure I can make promises as to how often a new contact will occur, weekly? Fortnightly? Monthly? The life of a spy (scholar) is hard. In any case, what information is being passed in this first contact?

Well, something about plausible and implausible deniability. Plausible deniability plays a prominent role in intelligence and covert operations. Governments try (or tried) to conduct their covert operations in a manner that is plausible deniable. They aim to be able to deny any responsibility for the covert operation in question. Plausible deniability comes in many forms. Already in the mid-1970s, Congressional investigators reviewing the activities of the CIA had distinguished between two types of plausible deniability. In one sense, plausible deniability aimed at hiding the government’s responsibility for a covert operation. In another, though, plausible deniability had expanded to protect the President and - at times - the CIA director. Here, what was being protected was not the government’s reputation but the president’s. A (controversial) covert operation might have gone ahead, but surely the president did not know about it. Michael Poznansky, a leading intelligence scholars, has called these the ‘state model’ and the ‘executive model’ respectively.

More recently, scholars have noted that governments are putting less emphasis on plausible deniability. They prefer to operate in a murkier environment, one characterised by grey areas, implausible denials, and disinformation. This “implausible deniability,” Rory Cormac and Richard Aldrich (two other heavy weights of intelligence studies) have written, permits states to still operate (semi)covertly, sending messages to their enemies, and showcasing reach and power, while also exploiting the ambiguity surrounding the operations and its perpetrators. Here, think, for example, of the poisoning in Salisbury of Sergei Skripal. It was followed by the implausible RT interview of the two suspects who - caught on CCTV - claimed they were in town to see the cathedral.

Cui prodest? Who benefits from it?

So what is new here? Most of the attention - when it comes to plausible and implausible deniability - is fixated on the perpetrating state. It is the perpetrating state that can act covertly and/or can exploit the ambiguity of its implausibly deniable operations. But what about the target states? And what about other states who are called to respond to these covert operations?

This passage from Mark Urban’s The Skripal Files is instructive. Describing the British government’s timid reaction to the assassination - in London - of Russian defector and Putin’s critic Alexander Litvinenko, Urban writes:

‘Downing Street did not want to endorse in any way Litvinenko’s dying accusation that it had all been done on Putin’s orders. As long as there were plausible alternative theories - from rogue elements in the FSB to organized crime - why paint yourself into a diplomatic corner that could easily derail the entire national relationship with Russia?’

And there it is, plausible and implausible deniability also serve the purposes of the target state (and other third parties). As long as there is some (im)plausible alternative explanation, why sacrifice strategic and political interests? Such an attitude can be found time and time again, for example, in governments’ reactions to state-sponsored assassinations. Why jeopardise strategic, economic, and financial interests and/or good diplomatic relations with one government, just to protect human rights and the right to life? Why indeed. This is all for now. I think our next contact will cover some of the troubles in relying on others to do your (dirty) job…

* ... at times hidden IN other items such as newspapers ...

Well done! Looking forward to your next piece.